Geoffrey Hinton's Nobel Prize and the Future of Pure Science

Geoffrey Hinton’s Nobel Prize and the Future of Pure Science

Today, Geoffrey Hinton, a professor at UoT and former AI research leader at Google, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics alongside John J. Hopfield for their achievements in Artificial Neural Network (ANN) research. Hinton himself admitted that this was somewhat unexpected, and there has been significant criticism from the physics community. While some argue that a Computer Science category should be added to the Nobel Prizes or that the Turing Award (considered the Nobel Prize of Computer Science) would have been sufficient, I’d like to approach this from a different perspective.

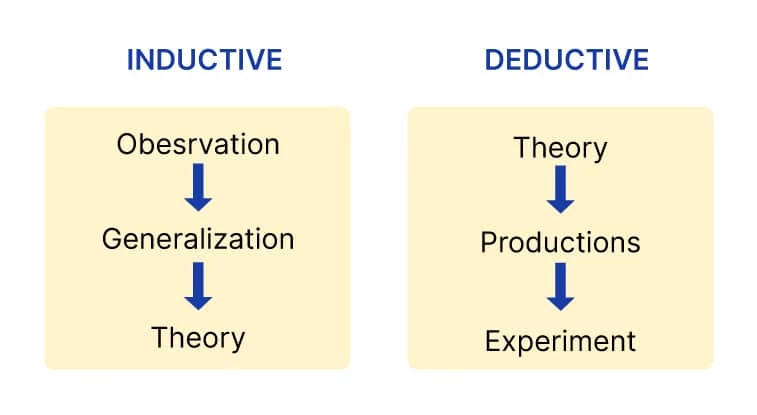

Inductive Reasoning vs. Deductive Reasoning

Inductive reasoning is the process of deriving generalized rules from observations based on experience. For example, observing various object movements in a gravitational field and deriving the laws of gravity is a good example of inductive reasoning. On the other hand, deductive reasoning is the process of uncovering relationships between propositions, such as revealing connections between axioms in a mathematical system and using these propositions to discover additional true statements.

Reasoning in Computation

Computers, as tools for deductive reasoning, have been able to replace a part of human reasoning that was once considered uniquely human. Through programming languages, we can design such deductive reasoning and accelerate it using computers. In contrast, inductive reasoning, which involves observation and generalization, has long been considered a uniquely human domain that computers could not replace.

Artificial Neural Networks and Inductive Reasoning

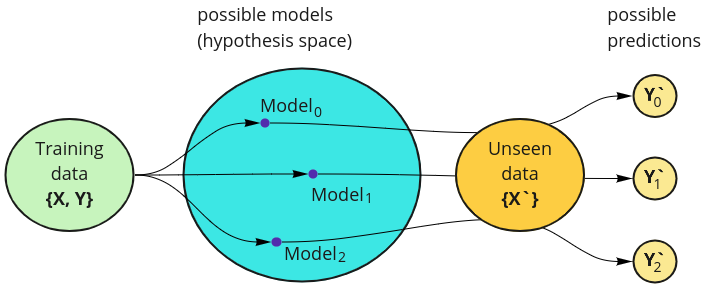

However, defying these expectations, the emergence of artificial neural networks and machine learning has provided a method to implement a universal predictor in machines based on data (observations). If there is data (observation) and the goal is precise prediction of a phenomenon, human inductive reasoning is no longer necessary.

Interpretability and the Black Magic Box

This shift inevitably changes the meaning of inductive methods or discovery in pure science. If the purpose of science is to predict phenomena, pure science will become increasingly obsolete. However, if the goal of science is to create knowledge in a form that humans can understand, pure science will remain valid despite AI advancements. To elaborate, while ANNs enable generalized predictors through data, trained ANNs are still not in a form that humans can interpret. They are merely tens of thousands to billions of parameters that emerged during the learning process. Therefore, we cannot understand the rules “discovered” by ANNs through data, nor can we use this information to find new truths (deductive reasoning). The generalized rules held by ANNs thus provide very limited information to humans. It’s like using software that cannot be reverse-engineered. In other words, it’s a choice between a “faster but black box predictor of reality” and “slower but understandable and usable knowledge,” and capitalism always chooses efficiency. Consequently, I believe that challenges to pure science fields will intensify in the future.

Conclusion

ANNs are not simply a computer technology. They represent a turning point where computers can essentially completely replace human intellectual reasoning, thus raising questions about the role of pure science in the future. In a situation where we have the means to predict all existing natural phenomena with high accuracy given sufficient data, complexity (number of parameters), and high-performance computers to process them, what will be the role of traditional pure science? I believe it’s time for the pure science field to find appropriate answers to these questions.